Are there hints of a Divine Council [of Gods] in the Old Testament?

Old Testament / History / Mythology

In the mythologies of the ancient world, the most supreme deity did not operate alone. Traditionally a male, he ruled over an entire pantheon of lesser deities, each with their own gifts or confined within their own dominions. This was especially the case in the old Canaanite tradition. So, it should come as no surprise if I were to say that some of that influence creeped into the thoughts and writings of early Biblical authors.

We have three major hints of a Divine Council present within the primeval portion of the Book of Genesis. It comes to us from the third and eleventh chapters of Genesis; more specifically, it is hinted at in the fall of man, when the human and his wife are banished from Eden, and the story of Babel, just before YHWH scatters mankind and confounds their languages.

3:22 And YHWH said: ‘Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil; and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever.’

6:4 The Nephilim were in the earth in those days, and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bore children to them; the same were the mighty men that were of old, the men of renown.

11:7 Come, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.

Who was YHWH speaking to in Genesis 3:22 when man and woman were banished from Eden? What does he mean by ‘one of us’? Does us mean the gods? Or what if originally, YHWH was a son of God himself? I am referring to Deuteronomy 32:8-9:

When the Most High gave the nations their inheritance, when he divided the sons of men, he fixed their bounds according to the number of the sons of Israel; but YHWH’s portion was his people, Jacob his share of inheritance.

Let us open our minds for a moment. The Most High in this case would be Elohim [1], the Canaanite El or Mesopotamian Ellil or even possibly Anu, while YHWH is the son of Elohim [2], a son of God. Whether this is the case or not, we do not officially know, and we may never find evidence to either prove or disprove this theory.

Hints of Henotheism in Scripture

Now, before I continue on the subject of henotheism [3], I wish to address a very important topic: the bene ha-elohim or sons of God in Genesis 6:4. This phrase has often been mistranslated as the sons of the gods, leading to some outlandish theories but as I will show below, within its proper context, that is not the case.

Let us ask ourselves the following question: while Elohim is plural in form, does it always have to be plural in meaning? We need to focus on three key areas: (1) grammatical indications throughout the rest of the text would help to determine if there is a singular or plural meaning within the word, (2) grammatical rules in the Hebrew language, and (3) its historical/ logical context. The English language is put into comparison with the old Hebrew. A great example would be that we do not have any other way of saying deer, sheep, or fish. This can be represented as both plural and singular, but it is the way we phrase it in a sentence that gives meaning and purpose. If you are talking about catching one fish, you would not state how you have caught many fish. The point that is trying to be made here is that evidence does in fact exist in the Old Testament where both cases have been used. Below are just a few of many examples to display these cases.

And God (Elohim) spoke all these words saying: ‘I am YHWH thy God (Elohim) who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.

Thou shalt have no other gods (elohim) before me.’

Exodus 20:1-3

Unto thee it was shown, that thou mightest know that YHWH, He is God (Elohim); there is none else beside Him.

Deuteronomy 4:35

…because that they have forsaken Me, and have worshipped Ashtoreth the goddess (elohey) [4] of the Zidonians, Chemosh the god (elohey) of Moab, and Milcom the god (elohey) of the children of Ammon;…

1Kings 11:33

God (Elohim) standeth in the congregation of God (El); in the midst of the gods (elohim) He judgeth.

Psalm 82:1

I said: Ye are godlike beings (elohim), and all of you sons of the Most High.

Psalm 82:6

Again, paying careful attention to the grammar in context tells us what form the noun Elohim has taken. The word means nothing until you observe the structure of the sentence in which it is used. This isn’t present in just the Hebrew grammar. Earlier Semitic languages such as Akkadian have shown evidence of this as well. In the Akkadian tongue, elohim translates to ilanu, also a plural form corresponding to the singular ilum. [5] One of the many cases of this term used in the plural form but holding a singular meaning comes from the Amarna Letters, which date to the 14th century BCE. One of the lines reads as follows:

sharri belya shamsya ilanya [6]

“the king, my lord, my sungod, my god”

Another thing about Hebrew grammar is that if a word appears with or without the article ha in a certain context, it can still be read as either a common or proper noun. It also applies to this case, where the term in question would literally translate to ‘sons of the God’ and not ‘sons of the gods’; signifying there to be only ONE supreme God. [7]

Looking back at the previous examples of Exodus 20:1-3 and Psalm 82:1-6, one cannot help but wonder what all the pluralities mean. Many scholars believe that this refers to the deities of the surrounding nations. However, questions still arise as to whether Israelite belief was originally henotheistic, where the supreme deity created and / or ruled over an entire pantheon of lesser deities. Does this point to cult worship in early Israelite culture, where in most cases YHWH was the more favorable deity of choice? The Christians have taken these pluralities as an argument for Trinitarianism. During the rise of Christianity, censorship was starting to be seen within rabbinical writings, and to mention the pluralities was a heresy.

Let us revisit Deuteronomy 32:8-9. There is something quite different observed in the Septuagint (hereafter, LXX). The Masoretic Texts (hereafter, MT) of the Hebrew Bible claim that the sons of men were divided according to the number of the sons of Israel; but the LXX reads: ‘angels of God.’

Before we continue, I would like to give a brief background on the MT. The MT is the Hebrew text of the Tanakh approved for general use in Judaism and also widely used in translations of the Old Testament. This standard was originally compiled, edited and distributed by a group of Jews known as the Masoretes approximately between the 7th and 10th centuries CE. Much of the work done by the Masoretes relies upon oral tradition, and differences are seen with the MT when compared to earlier sources such as the Greek, Samaritan [9] and Aramaic translations of biblical scriptures.

While the Samaritan Pentateuch (hereafter, SP) seems to agree with the MT, the Aramaic written 4QDeutj,n (found at Qumran [10]) reads ‘sons of God.’ And it just makes the topic a bit more complicated.

Bronze Age Ugaritic mythology states that the head of the pantheon, El (who, like the God of the Bible, is also referred to as El Elyon or “the Most High”) fathered seventy sons, setting the number of the “sons of El”. Assuming that this tradition of seventy survived into the Iron Age of Old Testament literature, the reading of Deuteronomy 32:8 where God divided the earth according to the number of heavenly beings coupled with the oldest surviving copy of the verse discovered at Qumran, it would just make more sense that we are talking about the same sons of God.

This leaves us with the puzzling questions: (1) Was early Israelite belief truly henotheistic? (2) If so, why were all instances hinting at one omitted from scripture? (3) Why are modern scholars referring to the sons of God as just angels of the Lord and not the forgotten pantheon of lesser deities? Here is an excerpt from an issue of Archaeology Magazine, which may help provide a probable explanation to the rise of monotheism erasing/ omitting all other deities from the biblical canon: [11]

…toward the end of the monarchy, there may already have been recognition of the usefulness of monotheism in the same way that the emphasis on the worship of Amun in Egypt during the New Kingdom (circa 1540-1070 B.C.) and Marduk in Babylon during the Neo-Babylonian Empire (circa 629-539 B.C.) arose. That is, it enabled the development of a powerful priesthood in support of all state religion and divinely inspired monarchy. Then came the fall of Judah and exile in Babylonia from 586 to 538 B.C. “Priests didn’t want to be out of a job,” she [12] proposes. “It was easier during the exile to say ‘Our god has defeated us, he is punishing us’.”

The Archaeological Evidence

This is a very difficult topic to discuss, because while plenty of archaeological evidence has surfaced over the years attesting to the fact that the Israelites and Judahites both worshipped Canaanite deities alongside YHWH within the region, was YHWH worshipped side-by-side with these deities in a true hierarchal pantheon? The evidence for other deities being worshipped in the land comes from discoveries of idols and seals, among other assorted crafts, and the use of theophoric titles [13] embodying both the Canaanite El (i.e. Jezreel, Elishua, Elishama, Eliada, Eliphalet, etc.) and Ba`al (i.e. Jerubbaal, Meribaal, Eshbaal, etc.). In biblical literature, we also have the worship of the Tyrian Baal under the rule of Ahab and his Tyrian wife Jezebel, which seems very likely, as I will explain below. [14] It should come as no surprise to the reader that both Israelite and Judahite states were never identical in language and iconography. In fact, linguistic analysis has proven that the Israelite Semitic language had originated or evolved from the Phoenician, while the Judahite was common among the southern Semitic dialects (i.e. Ammonite and Moabite) differing from the northern. A lot of this evidence derives from orthographical analysis, which I will be discussing much later in this book. Craftsmanship and trade display that there were very close ties between Israel and Phoenicia. A lot of Phoenician-influenced artifacts have been found throughout the land of Israel, primarily at Samaria. In fact, it is very difficult for scholars to differentiate between Phoenician and Israelite craftsmanship. It is generally believed that because Israel shared borders with the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon and Aramean Damascus, it kept control of the major trade routes that passed through its country, allowing it to be exposed to external influences. Starting from the middle of the 9th century BCE, Israel regularly joined with the Phoenician city-states along with the Arameans in anti-Assyrian coalitions. This is a clear indication that they shared common political and economic interests. [15] As a result of these close ties, specific religious themes were brought into the land, a lot of which was originally Egyptian. As time progressed into the first millennium BCE, these Egyptian influenced iconography evolved by adopting Syrian-Canaanite themes. So it would not be at all a stretch to assume that the Baal Shamem, or ‘Lord of Heaven,’ of the Phoenicians was the Tyrian Baal which Ahab adopted as his patriarchal deity ruling from his capital of Israel at Samaria.

Currently, the most convincing evidence that we have to display the worship of YHWH alongside a pantheon of other deities comes from a discovery, in the mid-1970s, at a remote spot in the northern Sinai Peninsula, Kunitillet `Ajrûd. This discovery led to a lot of controversy about YHWH having a consort. These archaeological findings consisted of two pithoi [16] dating from the 9th or early 8th century BCE, with inscriptions that read “YHWH and his Asherah.” It is still being argued whether this is a reference to the mother goddess of life in the ancient Canaanite religion.

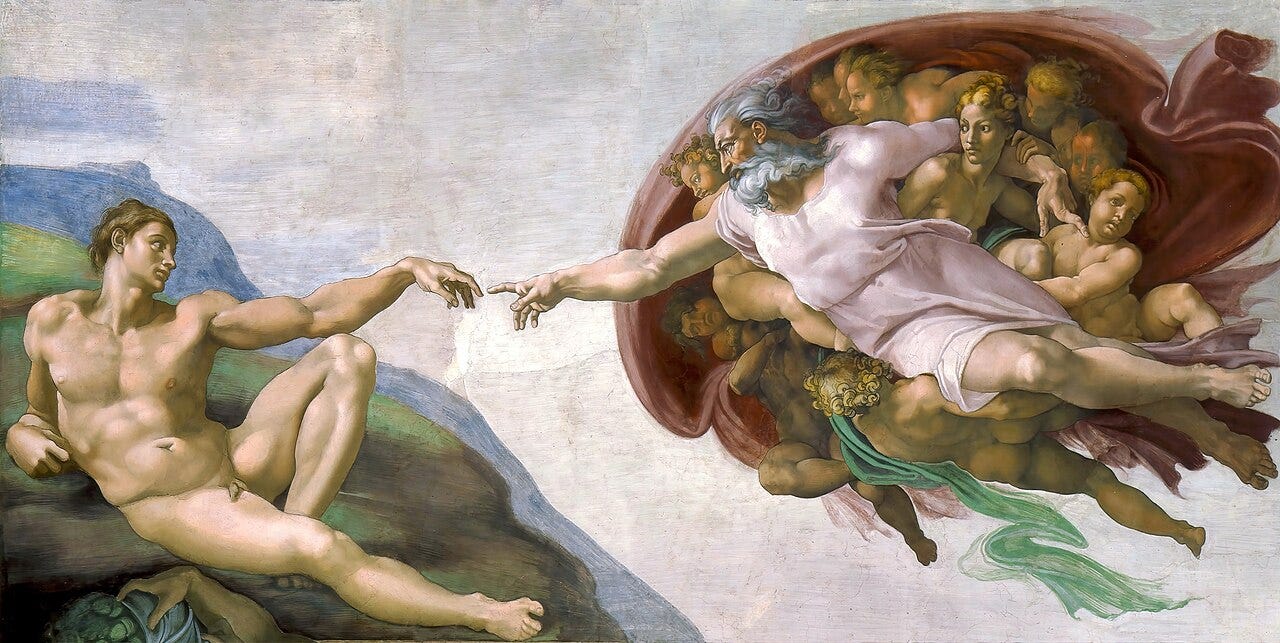

Featured image: Adam’s Creation Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni. (Public Domain)

Notes

[1] Elohim is the Hebrew word used to denote the supreme God in the singular but because it is plural in form, it can also be used to describe multiple gods.

[2] Its morphologically singular form is Eloah, while another common singular word for God is El.

[3] Henotheism is defined as the belief in one deity without denying the existence of others. Henotheism has also been called inclusive monotheism or monarchial polytheism.

[4] This is also plural in form and used when directly applied to the subject, but in this case it is used in the singular.

[5] Another masculine plural form to ilum is ilu.

[6] This too is plural in form, but the suffix of ya adds possession, signifying that the speaker is referring to the listener as his/ her god.

[7] Ruling over the possible lesser gods, the sons of God.

[8] The Septuagint is a Greek version of the Jewish Scriptures redacted in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE.

[9] Tradition holds that the Samaritan Pentateuch comes to us from the Abisha Scroll, purported to be written by Aaron’s son, but this obviously cannot be substantiated. As a result of grammatical and historical analysis (even with the Documentary Hypothesis in mind), the Samaritan Pentateuch is generally believed to have been compiled ca. 400 BCE.

[10] Qumran is an ancient ruin on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. In 1947 a Bedouin looking for his goats in caves stumbled upon several large jars, which contained ancient scrolls that have since become known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. These scrolls have become one of the most important finds in biblical history to this date.

[11] Scham, Sandra. “The Lost Goddess of Israel.” Archaeology Mar./Apr. 2005: 36-40.

[12] Diana Edelman; a biblical scholar.

[13] Theophoric (Greek: theos = god + phoreo = to bear) names are derived from or include the name of a deity. For example eliyahu which translates to ‘my God is Yah.’

[14] 1Kgs. 17-19.

[15] Keel, Othmar, and Christoph Uelinger. Gods, Goddesses and Images of God in Ancient Israel. Trans. Thomas H. Trapp. Minneapolis: Fortress P, 1998. 179.

[16] A pithos is a large storage jar.

I like Michael Heiser on this subject.